Early Career in Congress, 1941-1949

"We have seen the awakening of a new concept of Government--it is no longer a fantastic thing that existed apart from us, and sought merely to guarantee that we should not be molested in the enjoyment of our daily lives. We have seen government come to mean more than a safeguard of our individual liberties and possessions. We have come to look upon government as a positive force in the winning of economic betterment for all the people. It is no longer the servant of special interests--to speak or be kept silent as the interests of the ruling group might dictate. Government has become a positive force in the daily life of every one of us."

A New Deal Democrat

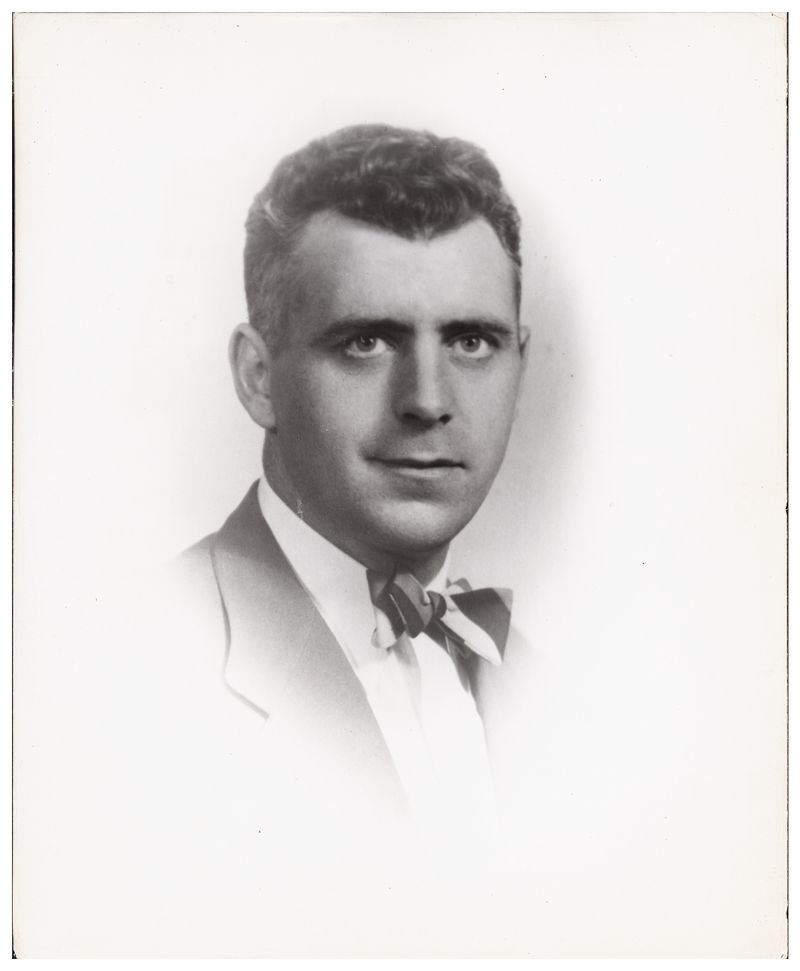

If a candidate such as John Fogarty--a twenty-seven year old, Irish-Catholic bricklayer with a union card--had run for Congress in 1930 instead of 1940, he almost certainly would have lost. The Republican Party had dominated Rhode Island politics since before the Civil War, and its political machine had become so corrupt that muckraker Lincoln Steffens profiled it in a 1905 essay entitled "Rhode Island: A State for Sale," in McClure's Magazine. Although residents of Irish, Italian, Portuguese, French Canadian, and other immigrant stock made up two-thirds of the state's population by 1900, several rules in the state's 1843 constitution prevented them from voting at many levels. Many of them labored in the state's textile mills and metal industries, but few had unionized, except for those in skilled trades such as bricklayers and masons, cigar makers, typesetters, and carpenters. The Democratic Party had almost no way to attain a majority in state and city politics and had sent only one senator and a handful of representatives to Washington between 1860 and 1920. It began gaining power after a big eight-month textile workers strike in 1922, when it billed itself as the "people's party." That year Democrats won major positions in the state government; by 1928, they had ended the voting restrictions.

By 1934, the Republican Party was rapidly losing support in many states as the Great Depression deepened. Democrats, inspired by President Roosevelt's pro-labor New Deal policies, went after the working class vote with help from the unions, and broke the Republican hold on Rhode Island. Governor Theodore F. Green led a "Bloodless Revolution" that quickly dismantled the Republican machinery and completely reorganized the state government. The Democrats also made many reforms to improve conditions for workers, including a minimum wage for women and children, a shorter work week, and old-age pension plans. In 1936, both of the state's U.S. Senate seats and its two House of Representative seats went to Democrats. They lost the House seats again in 1938, but regained them in 1940. Rhode Island would not elect another Republican to Congress until 1976.

Young John Fogarty in many ways embodied this rapid Democratic Party ascendance in Rhode Island and the political, economic, and social priorities of the New Deal era. He knew firsthand how precarious workers' lives could be; he had watched his father struggle to support six children, and had entered the workforce during the worst years of the Depression. He and his family had not starved, but they knew many families who weren't as lucky. In his first term in Congress, he was an aggressive advocate for labor's interests. While he supported Franklin D. Roosevelt's domestic policies, prior to the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, he voted against some of the president's war measures, such as arming merchant ships against German submarines, and extending the length of military service. After America entered World War II, he supported the rights of war-industry workers who threatened to strike, although some critics called this unpatriotic. (A United Mine Workers strike in May 1943 prompted passage of the Smith-Connolly Act (aka the War Labor Disputes Act) later that year, which placed extra constraints on strike actions.) Fogarty's first committee assignments were to the House Naval Affairs Committee and the Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee. Both were good assignments for a representative of a state with five naval bases and large fishing industry. The Naval Affairs Committee was one of several congressional groups charged with monitoring the efficiency and welfare of the huge new workforce created by America's rapid mobilization for war. Committee members traveled extensively, looking into the living and working conditions of naval personnel and workers in various Navy- related industries, and investigating manpower problems as well as workers' access to adequate housing, transportation, schools, and medical care.

Late in 1943, Fogarty, concerned that committee members were not getting the whole story on their official visits to naval bases, proposed that he take a leave of absence from Congress to join a Naval Construction Battalion. As a "Seabee" he would be better able to see the enlisted men's true situation. President Roosevelt discouraged the plan--there was no provision in congressional rules for such actions. Nevertheless, in December 1944, soon after winning a third term in Congress, Fogarty resigned from the House and enlisted in the Navy. (The 78th Congress had concluded its business, and there was no deadline for delegates to take the oath of office for the next Congress, so Fogarty was allowed to resign, serve briefly in the Navy, then resign from that service and take his oath for the Congress when he returned.) For about six weeks, he served--under cover--as a carpenter's mate with a battalion in the Mariana Islands. Most Seabees were in the construction trades (and unions) before the war, and Fogarty easily passed as one of them. He talked to the other Seabees as they worked together, listened to their concerns, and learned that the main complaint was being overseas for years at a time, with little news of the home front. When he returned, he introduced measures to expedite the return of all American troops after eighteen months of overseas deployment. Reactions to Fogarty's short-term Navy service were mixed: some of his constituents were (understandably) concerned about who would represent them in Congress while he was gone; critics questioned his motives, calling the short leave of absence a political publicity stunt. Letters from enlisted men, however, praised Fogarty for demonstrating his concern by working among them, and thanked him for raising their morale.

Fogarty's committee work just after the war took him to Europe (where the group helped assess the need for postwar U.S. aid), to Panama (to assess postwar needs of the Canal Zone), and on tours of the U.S. bases in the Pacific. He also served on a committee that studied postwar economic policy and planning.

Appointment to the House Appropriations Committee

Like many young members of Congress, Fogarty wanted to serve on one of the House Appropriations subcommittees. The Appropriations Committee members decide how the government's annual budgets will be doled out, and thus have much influence on the agencies they fund. For his fourth term in 1947, he asked to be assigned to the Defense Department sub-committee, but to his disappointment, was assigned to that for the Department of Labor and the Federal Security Agency (later the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.) Initially, Fogarty was often bored by the FSA part of the work. That began to change as he worked with Frank B. Keefe, the Wisconsin Republican who chaired the Labor-FSA Committee. Keefe was passionate about improving the nation's health and believed that the federal government--which had become very active in research during the war--must maintain or even expand its role in medical research and public health, rather than return to the pre-war status quo. Several of the FSA's component programs would become the main vehicles for such changes.

The Federal Security Agency included the Social Security Administration, the Public Health Service (PHS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Education Office. Within the PHS was the National Institute of Health (singular), then a rather modest medical research establishment with one named institute (the National Cancer Institute, established in 1937) and a pre-war (FY 1941) budget of just $711,000. Before the war, this seemed like plenty of money to many observers: scientific and medical research in America was typically a part-time enterprise, carried on by university and medical school professors in addition to teaching. Most public health work--from sanitation to disease control and prevention--was done at the state and local levels. Targeted research-- e.g., to develop vaccines for polio or yellow fever, or new drugs--was usually funded by private foundations or pharmaceutical companies. Even with the great expansion of federal programs during the Depression, many saw little reason for the government to get involved in large-scale funding of research.

Wartime experiences forced a reassessment of the American health care system, the state of American science, and the role that the federal government might play in those areas after the conflict. First, as they mobilized for war, Americans discovered that fully one-third of the young men who enlisted in the armed forces had to be rejected for medical reasons, showing that health services were far from adequate. Physicians, nurses, and other medical personnel were also in short supply. In the final years of the war, leaders started looking ahead and realized that the nation's hospitals would be hard-pressed to handle the thousands of returning veterans, or the expected population boom. Senator Claude Pepper held hearings in 1944 to assess the health of Americans, and start planning for peacetime. Priorities included medical research, training of more health personnel, and construction of more research and medical care facilities. In 1946, Congress passed the landmark Hospital Survey and Construction Act (also known as Hill-Burton Act) to support building more hospitals. Federal involvement in health care and research was also being demanded by some of the private-sector organizations and their leaders. Chief among these were philanthropist Mary Lasker and her friend Florence Mahoney, who got to know Pepper and several other legislators, and helped convince them that funding research on the two big killers--cancer and heart disease--was one of the best ways the government could improve the health of Americans.

Even as it exposed the shortcomings of America's health care, the war also demonstrated the crucial value of large, intensive, government-run research programs. The Allies' victory was made possible partly by such programs, which developed the large-scale manufacture of penicillin, blood banking, radar, and the atomic bomb, among other things. During the war, the government had for the first time a clear research policy and a centralized system for carrying it out. The Office of Scientific Research and Development was created July 1941, incorporating the National Defense Research Committee and the Committee on Medical Research (CMR), to coordinate programs in weapons development and medicine, respectively. In post war planning, it was decided to give the Public Health Service the same kind of authority that the Committee on Medical Research had during the war: to pay for research performed by universities, hospitals, laboratories, and other public or private institutions; and to support such research through grants, rather than contracts, and to individual researchers. And after the war, the PHS took over all the remaining medical research contracts from the CMR and the NIH budget increased to about $3.5 million in FY 1946 and $8 million the next year.

Frank Keefe, like Edward Thye, who chaired the Senate Labor-FSA appropriations committee, argued that the national interest required generous investment in public health and medical research. He also argued that appropriations committees should not be bound by the usual pre-war appropriations routine. Traditionally, the President, his cabinet members, and the Bureau of the Budget generated a federal budget each year, and the appropriations committees, as stewards of the public purse, pared it down. In hearings, the heads of agencies and programs were asked to justify the administration's estimates. Keefe, however, believed that little would get done if researchers were just "fiddling along" with modest annual budget increases. He insisted that Congress and its committees had a right to know what funds individual programs genuinely needed to make substantial progress, and he prodded the agency heads to ask for those figures and not be cowed by the Bureau of the Budget. Likewise, he argued that Congress must not allow the Bureau of the Budget to water down congressional initiatives by reducing budgets unnecessarily. Fogarty soon adopted Keefe's approach to budget matters, along with a key principle: if sub-committees wanted to encourage progress (instead of just automatically reducing budget estimates) they must have the backing of the ranking members of the opposite party. As historian Stephen Strickland has noted, "Implicit in all this was the rule that health programs, and especially medical research and disease control programs, were never to be presented as partisan matters . . . " even if committees sometimes divided along party lines regarding spending levels.

Using these tactics, Keefe and his committee increased many of the FSA budgets dramatically for fiscal years 1948 and 1949. The NIH appropriation went from $8 million to over $28 million, and NIH added the National Heart Institute and the National Dental Research Institute in 1948 and the National Institute of Mental Health in 1949. These increases were balanced by judicious trimming of other FSA program appropriations.

It's not clear when Fogarty became fully committed to public health and medical research. His friend and colleague Melvin Laird has suggested that the turning point came fairly early, when the subcommittee appropriated funds in 1947 to support important clinical trials on streptomycin, a new antibiotic that cured some types of tuberculosis. Certainly, in those first few years on the committee, Fogarty made the connection between health care, research, and the welfare of working people.

The Democrats won a majority again in the 1948 election, and in January 1949, Fogarty became chair of the Labor-FSA appropriations subcommittee. Keefe, as ranking minority member, would continue to mentor him during the first two years, before retiring in 1951.